The Power of Reflection: Applying The Five R’s for Student Success

Laurie L. Hazard, Ed.D., Department of Humanities and Social Sciences, New England Institute of Technology

Each new student enrolling in college brings their unique forms of knowledge, skills, and abilities to the experience. Many first-year students will experience a smooth transition, but some will encounter a variety of challenges, and others may even need to reconcile failures along the way. No student goes off to college dreaming about failing – most students approach their college transition with optimism and aspire to make the dean’s list. So, what factors influence their success?

As many of us have observed, first-years will need support to help them think more deeply and critically, not only about the difficulties they may encounter, but also to reflect on how to cultivate their strengths in an effort to mediate the patterned challenges that inevitably will arise with the college transition. As student success practitioners, we can help students anticipate these typical challenges and offer them tools and problem-solving strategies to resolve them before they get in the way of success.

The first step is to encourage students to reflect on their day-to-day experiences as they traverse their first year. John Dewey, an American philosopher and educator argued that we don’t learn from experience; rather, we learn from taking the time to reflect on our experiences (Dewey, 1916). Indeed, reflection is a powerful tool to help students learn, change, and grow. Drawing from research and practice, Hazard (2025) has developed a pedagogical framework to guide student success professionals in their efforts to help first-years navigate the college transition and learn to reflect more deeply about their adjustment. This framework highlights five key skill sets that students need to be successful and embeds reflection as the foundational habit necessary for the development of these skills. Indeed, teaching students the Five Rs for Student Success offers a powerful reflective approach for students to apply to their college experience.

1. Recognize: Knowing Yourself and Learning About Anticipatory Problem Solving

Emotional intelligence includes the ability to recognize, understand, and manage emotions. High emotional intelligence has been linked to improved mental health, greater self-awareness, and enhanced problem solving and decision-making skills, all of which are crucial for college success (Hazard and Carter, 2025). As student success professionals, we can teach students about emotional intelligence, asking them to consider how well they know themselves as students and whether they feel ready for what’s ahead. Additionally, we can help students recognize and develop their intrapersonal skills, a dimension of emotional intelligence.

Start by encouraging first-year students to reflect on their secondary education. What courses did they feel confident in? What courses presented challenges and why? Looking back on their experience, would they have approached anything inside or outside of the classroom differently? After time has been given for this reflection, ask students to apply their experiences to what may lie ahead for them in college. One activity would be to have students closely examine their first semester schedule and course syllabi. Ask them to choose a “target course” (i.e., one they anticipate will be the most challenging) and how they can set themselves up for success. For example, if the course has a heavy reading load, what strategies can they employ to ensure that all readings are completed on time? If the course is a math course, what campus resources are available to boost their quantitative skills?

Once they identify their target course, the next step is to help them think about what made this subject area challenging in the past. Ask them what potential actions and behaviors they could enact to prevent problems from arising. Perhaps it’s using time management strategies to project and plan their reading load for the week. Psychologists call this approach anticipatory problem-solving.

Students who possess a strong understanding of themselves and recognize their intrapersonal skills are more likely to excel at anticipatory problem-solving. Assure students that they can actively work to get to know themselves better. While some students may already feel that they know themselves well, it’s important to remind them that college provides opportunities for the growth and development of problem-solving skills. For instance, what did they do in the past when they experienced stumbling blocks? Were they reticent to ask for help or were they comfortable with reaching out?

Remind students that there are resources on campus purposefully designed to help them with any stumbling blocks that they may encounter. We can assist and teach the students how to access resources for their target course and more. Point students to office hours and to tutoring support. Instead of waiting for challenges to arise, encourage them to be ready for them, prepare to face them, and know where to seek help. In other words, we can help students to reflect on and develop their self-advocacy skills.

2. Reach: Developing Self-Advocacy Skills

Student success practitioners can normalize that it is okay to ask for help and educate students about the various resources on campus that are designed to assist with specific student needs. Explain to them that campus experts are available to provide support with the Six Areas of College Adjustment: social, emotional, financial, intellectual, academic, and cultural (Hazard and Carter, 2019). Help them draw a connection between the areas of adjustment and key resources designed to help. From peer tutors to research librarians, to advisors, there is ample assistance. Still, students are sometimes reticent to ask for help for different reasons. For instance, acknowledging that different cultures have varying perspectives on help-seeking behaviors will encourage students to reconsider the benefits of asking for assistance when they are struggling. Assure students that, in college, experts on campus expect them to ask for help and are eager to assist.

One approach is to introduce the concept of self-advocacy. Define what it is and how developing self-advocacy skills can help them in their collegiate career and in the future. Identify the components of self-advocacy 1) speaking up for themselves, 2) learning where to get information, 3) determining who will support them, 4) knowing their rights and responsibilities, and 5) understanding self-determination; that is, their ability to make their own choices and decisions.

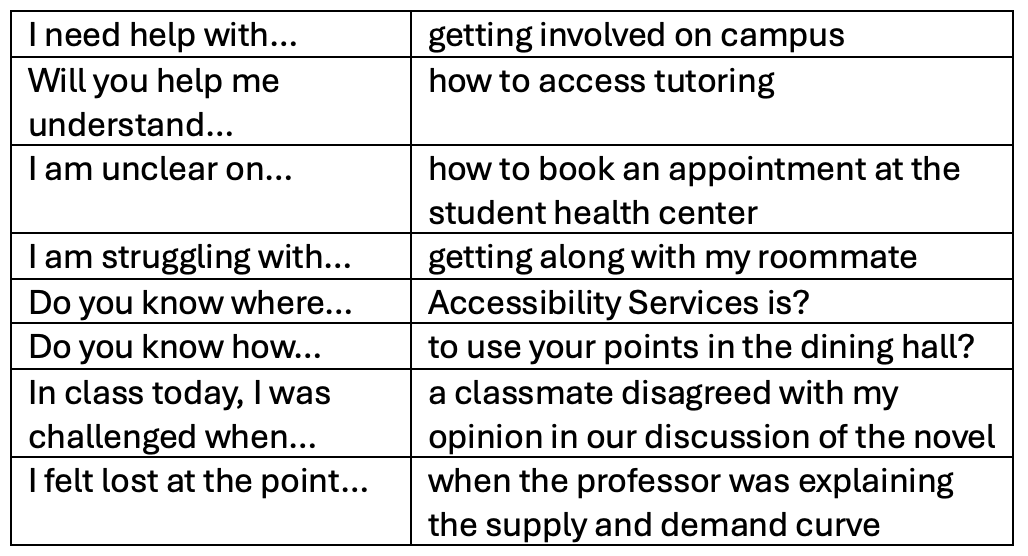

A simple classroom exercise is to provide students with prompts to practice their self-advocacy skills with. Students can record responses to the prompts on their own, pair and share, or get into groups and identify the areas where they need help

Table 1

Prompts to Practice Self-Advocacy Skills

Not only does this exercise allow students to practice their skills, but it also builds their self-confidence to speak up and allows insights into the areas where they may be struggling. Once student success professionals determine what their struggles are, we can help them access information and support. Helping students develop self-advocacy skills enhances their ability to navigate challenges.

3. Realize: Processing “Disorienting Dilemmas”

Helping students realize that they have agency and can solve their own problems also increases their autonomy by empowering them to communicate and articulate their needs effectively. The concept of disorienting dilemmas in Mezirow’s (1978) Transformative Learning Theory offers students a process for working through and articulating their challenges. According to Mezirow (1978), students face challenges when experiences do not fit with their pre-existing meaning structures. Transformational learning occurs when their meaning systems are discovered to be inadequate in accommodating a life experience. Our role is to “ready” students to replace former meaning systems with new perspectives.

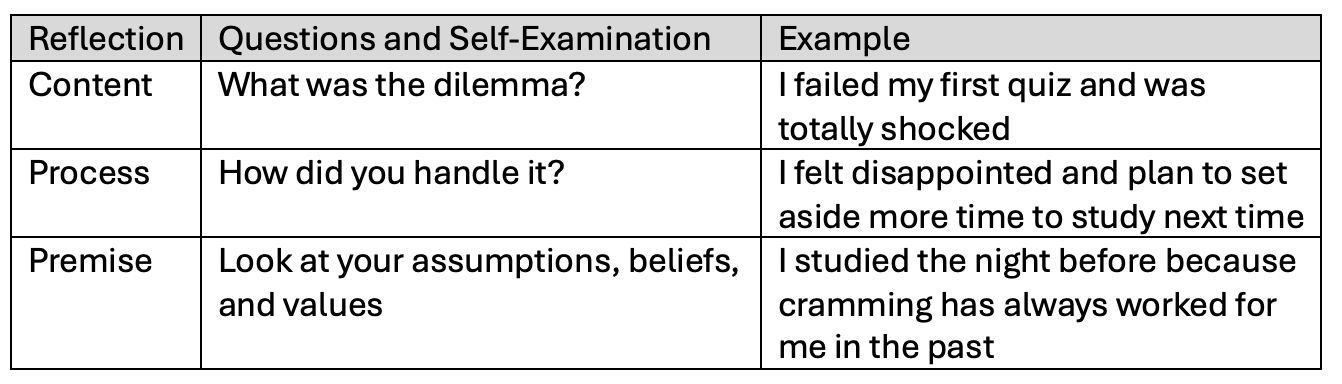

Teaching students about disorienting dilemmas and how to process them provides a roadmap to work through challenges. Processing disorienting dilemmas involves three types of reflections: content, process, and premise. Using real-life examples from students’ own college experiences is a beneficial way to process disorienting dilemmas. Here’s an example of the dilemma of failing a quiz:

Table 2

Types of Reflection for Processing a Disorienting Dilemma

In this case, the student believes that augmenting study time will solve the problem of the failed quiz. The assumption is that applying the strategy of studying the night before should work. The student applies a secondary education meaning system to the college experience assuming that cramming will suffice in college. The solution is to replace the current meaning system; teach the student about how spaced practice and studying incrementally is more effective than massed practice or cramming.

Model your own experiences of processing a disorienting dilemma and then help students to practice processing their own using the three types of reflections. Ask them to choose a past or a present challenge, utilize the reflection strategy to process the dilemma, and then brainstorm solutions. Reflecting on disorienting dilemmas will not only help them tune into their own values and beliefs, but it will also begin to uncover what other types of factors may be impeding their success too.

4. Remove: Considering Internal and External Factors Related to Success

Students’ values, beliefs, attitudes, and feelings are internal factors that may mediate student success. However, external factors, like an unhealthy relationship or a chaotic environment, can also play a role. Students need to reflect on both internal and external factors that mediate their success. Bandura (1978) identifies the relationship between internal and external factors as reciprocal determinism.

Individuals have the power to shape their environment, but the environment can also influence individuals’ behaviors. Have students think about trying to study in a bustling coffee shop or in their rooms when their hallmates are having a party on the floor. Students can choose to put themselves into highly distractible environments, or they can remove themselves from the less-than-conducive environment for exam preparation.

Challenge students to consider how they might be influenced by their new environment in college. To do so, they must consider the wide variety of influences, such as friendships and college culture, and how a wide variety of factors might affect their college experiences. While not an exhaustive list, here is a simple tool to help them begin to analyze these factors:

Table 3

Internal & External Factors Related to Student Success

For first-year experience courses, a simple activity is to ask students to consider which factors may impact their success and how. Ask them to consider how some of these factors can either positively or negatively influence their success depending on the situation. Brainstorm strategies and resources on campus designed to support students to help them remove any obstacles that arise. We can teach them how to activate a plan. The plan may involve reaching for their self-advocacy skills.

While not every factor is under the students’ control, encourage them that asking for help is a step toward allowing them to get connected with an advocate on campus who may be able to assist them in navigating challenging situations. Advocates come in the form of first-year experience instructors, advisors, peer mentors, resident advisors, and more. What better way to address challenges than enlisting the support of a peer who’s had a similar experience, or the guidance of a professional who’s worked with countless students on plans for success.

5. Results: Assessing Outcomes

Even if they are open to change and growth, every college student will encounter factors that may impede their success. Instead of brushing these issues aside, it is important for students to take accountability for their role in situations where they did not achieve desired outcomes. For example, a student received a low grade on a research paper that they started working on two days before the deadline. In this situation, the student may wish to revisit their time and behavior management techniques. Did they know the deadline was coming? Did something pop up that distracted them from starting their paper earlier? How can they complete more research next time? When students consider the results of their actions, it’s important for them to apply their intrapersonal skills, self-reflect, and be honest about what they could have done differently in the situation. Similarly, as instructors, it’s our job to ensure that we are setting our students up for success. Taking into consideration the example above, you, as the instructor, assign a research paper to your class of twenty students. As you’re grading, you have some papers that are great, but the majority seem to have missed the mark. In this situation, you could ask yourself: Did I clearly communicate the assignment and my expectations for it? Was the rubric that I used fair? Did my students know how to access the correct resources on campus for their research? Reflection can be just as important for instructors as it for students.

Taking a psychoeducational approach and teaching students about the power of reflection offers students the tools to recognize their potential. Utilizing the Five R’s of Student Success provides a practical framework to help student success professionals lead students to greater self-awareness, improved problem-solving capabilities, and to an increased understanding of what will enable them to achieve success in college and beyond.

References

Bandura, A. (1978). The self-system in reciprocal determinism. American Psychologist, 33(4) 344-358

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. Macmillan Publishing

Hazard, L., & and Carter, S. (2025). The habits of mind for success in college: Claiming your education. Kendall Hunt Publishing Company

Hazard, L.L. & Carter, S. (2019, November). The changing family dynamic and student success: A theoretical framework. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual National Symposium on Student Retention.

Mezirow, J. (1978). Perspective transformation. Adult Education, 28(2), 100-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171367802800202

How to cite this article:

Hazard, L. L. (2025). The power of reflection: Applying the five R’s for student success. Insights for College Transitions, 21(1).